by Ben Kemp, Grant Cottage Site Coordinator

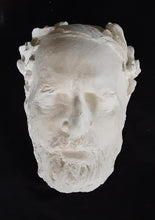

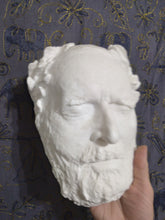

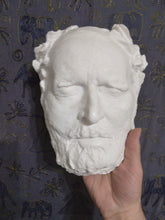

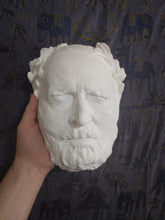

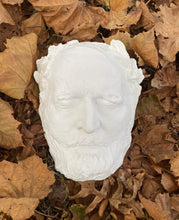

On July 23, 1885, amidst the immediate fury of activity surrounding the death of one of America’s greatest and most famous heros, there was an artistic endeavor quietly taking place. A 32-year-old sculptor was making a plaster cast of the face of the recently passed U.S. Grant at Drexel Cottage on Mount McGregor. Around since antiquity, the taking of masks of the recently deceased was done for various reasons, frequently to use as a model for later sculptural works of the subject. By the 19th century, the masks themselves became a valuable memento and memorial of the departed.

Karl Gerhardt, born in 1853 in Massachusetts, worked at various jobs and even served a stint in the army. Beneath the modest exterior hid the talent of a true artist. By 1880 Gerhardt had married a younger woman, Harriett “Hattie” Josephine Gloyd, who encouraged her husbands artistic side.

It was Hattie who contacted Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) to invite him to see her husband’s work. Clemens was so taken with Gerhardt’s work that he personally funded his education. In the spring of 1881, the Gerhardts set off for a prestigious art school in Paris, where they continued to receive monetary and psychological encouragement from Clemens for the next few years.

In July of 1884, Karl returned to the U.S. determined to obtain commissions in hopes of repaying his benefactor Clemens. That summer Gerhardt sculpted a fine bust of Twain to be used for the frontispiece of his novel Huckleberry Finn.

Image courtesy Cornell University Library

Twain and Gerhardt visited the ailing General Grant in his New York City home in March of 1885. Twain had already secured the contract to publish Grant’s memoirs and the family was shown a clay bust Gerhardt had made of Grant from a photo. The family was impressed and Gerhardt was allowed to model General Grant for a life bust. Perhaps Grant, while sitting for Gerhardt, remembered his own unrealized endeavors as an artist. Grant himself had completed drawings and paintings in West Point that showed true artistic talent. There was an intention of selling Gerhardt’s bust of the General by subscription (the same method Twain was using to sell Grant’s memoirs), but there’s little evidence that it was profitable. Regardless of its profitability, the family was very pleased with the outcome of the bust. Clemens and Gerhardt were both displeased, however, when rival sculptor Rupert Schmid was allowed access to the General for a study soon after.

In April 1885, with the end of Grant’s life only a matter of time and the trust of the family, Gerhardt secured the commission from Fred Grant to take the death mask of his father. In June Gerhardt traveled from his home in Mt. Vernon, NY to Mt. McGregor to be close to the fading General. While staying at the nearby Balmoral Hotel, he kept Clemens appraised of the situation on the mountain. Gerhardt bided his time by working on an additional study of the General and a bust of Nellie, the little daughter of Grant’s youngest son Jesse. The bust of Nellie turned out well and the family was pleased and wished him to stay on to finish the other. Karl must have been enamored with his famous subject as he wrote Clemens on June 26 that he “shook hands with the Genl yesterday and he remembered me."

In late July some tension arose between Gerhardt and the Grants, but Hattie and child arrived on the 19th and smoothed things over with the family. On the 23rd Gerhardt made his first death mask. He would later write to Clemens, “Imagine the trembling Gerhardt taking is first death mask, and from such a personage--It is only nice to think that no one else did it the family did not wish it… Dr. [John] Douglas saw the mask as did the Mexican minister [Leon Romero] and both pronounced it an unusually fine one… The sketch I have not touched since the 23rd the day he died. I had draped it all before that and everybody's enthusiastic over it. I am casting it now.”

In a testament to the popularity of Grant and the competitiveness of the art scene at the time, Gerhardt reported to Clemens a few days after Grant’s death that guards had to be posted at the cottage to keep out sculptor Rupert Schmid. Schmid had supposedly threatened “he would have a mask at any cost” and disparaged the young sculptor as unqualified to make such a prominent work.

Gerhardt would experience a sudden burst of fame as “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated” featured a front page depiction of the sculptor at work making the mask. The fame would be fleeting however as the question of ownership of the mask was uncertain and created a heated controversy. In the end Clemens would forgive the thousands of dollars of debt owed him by Gerhardt in exchange for transferring the mask to the Grant family.

Gerhardt would go on to complete works that would adorn Twains’ Hartford, CT home, city and town parks and even a few on the Gettysburg battlefield including the iconic Gouverneur Warren statue on Little Round Top. None of these, however, would bring lasting fame or fortune, and after losing his wife in 1897, Gerhardt would move south to Louisiana. After years away from sculpting, Gerhardt would return to the trade but remained in obscurity until his death in 1940.

An artist who sculpts the human form not only establishes a lasting legacy for himself, but even moreso perpetuates the memory of his subject. Grant, who in life was referred to as being a “man of stone,” a man of iron will and determination, now had his final likeness preserved in sculpture for the world to see and remember.